Am I Going Fast Enough Yet?

Finding peace in artmaking inside crip time

First, I’d like to acknowledge the horrors that so many are undergoing this week. The cruelty in Palestine and Lebanon is never-ending and every day more unfathomable. The grief and exhaustion in the Southeast after Hurricane Helene’s destruction is deeply painful to witness, no less so because I called Greenville, SC home for two years. We are no one without each other, and we must stand side-by-side at this time.

eSims are still needed in Gaza.

Mutual Aid Disaster Relief is helping post-Helene.

I haven’t been keeping up with my newsletter, because I’ve been exhausted.

Since October 2023, I’ve been working incessantly on book edits. I rewrote the book top to bottom three times in a year. Laboring like this feels complicated. On the one hand, the book has grown past my expectations and has gradually become closer to the book of my heart. On the other hand, I find my heart floating around, unsure where to go and what to do. Unmoored, as it thinks only about work these days.

It isn’t a new concept to point out that working on the publishing part of the bookmaking process isn’t always as nourishing as the initial, dreamier parts of constructing a story. Yes, revision has its own joys, but I’m also mired in conversations—sometimes even just with myself—about timelines, pub dates, comps, how to stand out in the market. Unlike in the before book deal times, any fruitful exploration I am doing is also accompanied by the fearful internal chant of this is due soon, this is due soon, get it done. It is difficult; and, as a disabled writer dealing with at least two physical illnesses and one debilitating mental one (the enumeration of this is sticky to do; the body and mind are connected, but what I am attempting to do is give you a sense of the (un)wellness considerations I carry alongside me) I also have to endeavor to balance this stress with my responsibilities to myself.

In a great Substack essay titled “The inside and the outside,” Emma Copley Eisenberg says,

It’s no great insight to say that writers actually have three jobs despite appearing to only have one:

1. To write.

2. To have written, aka to publish—to perform the role of the human person who completed the first job; to participate in and possibly to increase the likelihood that your writing will reach readers and “succeed” within capitalism.

3. Whatever else you do to make money and to continue to have a body and mind that can do the first two jobs.

This last point is of interest to me as I continue to navigate how work hijacks my body. To be clear, this isn’t to say that I find writing in its purest form (Eisenberg’s Point #1) to be taking an incessant toll on me. If I thought that, I wouldn’t be drawn to it in the way I am. Stories come to me like great loves, walking through my day with me, no matter what I do. But I don’t just live in a reality in which I can fantasize about my characters moving through their universes in ways that excite, move, and confuse me. Instead, I live in a reality where I have to give as much energy to Points #2 and #3 as #1.

When it comes to making a living, most of my income comes from my full-time day job at a university. This means thirty-five hours a week in which I take responsibility for students and make sure they graduate, along with other tasks. I am not someone who can do things she doesn’t care about at all, so I do feel an affinity toward my day job. However, I am ultimately interested in holding onto it because of the security it affords me. When I tell people about this job, they often say, “Ah, yes, someone has to do it, right?” And I want to tell them, “Yes, and that person has to be me because I get good health benefits from working. I get retirement, which I need to accumulate because I have very little guarantee that I’ll be healthy enough to work late in my life. I get PTO and sick time, which I need to attend doctor’s appointments.” How else can I have a “body and mind that can do the first two jobs”?

Working full-time intersects oddly with book edits, particularly when they are extensive. From June to September 2024, I spent my days working from 8 AM to 4 PM or so, depending on the day. Then, I’d come home and take a small break to talk to my husband. Then I’d work again. Then, a small break for dinner and thirty minutes of leisure time. Then work again, until 10 PM. I would sleep after that because my body demanded it. On weekends, I worked as well. When we traveled, I took my computer and then mentally beat myself if I couldn’t get the things done that I had said I would. For some people, this schedule might work; for me, working sixty-plus hours a week took an immense toll on my mental and physical health, especially while I was trying to manage disconcerting issues like pain, somehow both stinging and numbing, up and down my whole body; reworking my medications; my family; my friendships; my new therapy modality; starting and keeping up my TikTok presence because it’s good marketing; taking on readings and workshops because it’s part of what writers do; and then engaging with all the random noise of adulthood that comes in one’s thirties.

Perhaps as you read this, you understand the difficulty that I am describing; perhaps not. It is often easy to say “I could do this” or “I have more going on than that,” but I challenge you to put aside those mindsets and instead enter into the ethos of “crip time,” a term coined by Alison Kafer in Feminist, Queer, Crip. “Rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds,” she writes. Crip time requires us to rethink the clock in so many ways, and it requires us to understand that time operates disparately for others. In “Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time” Ellen Samuels says:

When disabled folks talk about crip time, sometimes we just mean that we're late all the time—maybe because we need more sleep than nondisabled people, maybe because the accessible gate in the train station was locked. But other times, when we talk about crip time, we mean something more beautiful and forgiving. We mean, as my friend Margaret Price explains, we live our lives with a "flexible approach to normative time frames" like work schedules, deadlines, or even just waking and sleeping.

Samuels continues with examples of crip time as time travel (in a pool, she does water exercises with seniors and considers how she looks young and yet her body is also old), of crip time as grief time (it is the time of thinking of loss, missing the body as it was, but also not wanting to give up what is), of crip time as broken time (disabled people are forced to break their understanding of time and how they live in it), and more.

To this list, I’d like to add that crip time is committed and uncommitted time. As Samuels outlines, disabled people have no choice but to commit time to things that abled people do not. In my case, the extra twenty to thirty minutes in the morning, perching on the cold toilet when my colitis is acting up; the unexpected hours I need to wait past my appointment start because the blood draw line is long; the extra minutes I take to breathe and resist an OCD compulsion; the time to message the nurse back and forth and understand her directions; the hour on the phone with insurance making sure a procedure will be covered; the extra rest I have to take when my POTS is flaring and my heart rate is spiking high. These non-negotiable commitments require me to over-commit to my body and my health, and thus, there is an inherent tension between this and how much I would like to commit to other things as well. Too, there is an inherent tension in how others perceive my commitment—or our lack of commitment, as the case may be—to what they care about.

Last year, I spoke to my employer about accommodations for my day job (a process that I’m not aware formally exists within publishing and that rather must be negotiated by one’s self or, if one is lucky, by their agents—another topic I look forward to writing about, so let me know if you know something I don’t!). I did receive these accommodations—more flexible work hours that would help me manage when I was stuck in the bathroom or in severe pain—but not without a lecture about how I needed to make sure I was getting my work done. A lecture, that did not include any sympathy about how my getting my work done required extra effort that others did not have to take on. A lecture, that did not consider that I am well aware that I need to keep my work at “standard” because if I lose my job and health insurance, I may then lose access to important care that I need. (A note here that I am lucky that I am married and have that safety net of my husband’s medical benefits; however, so many disabled people are not even able to marry because of how disability benefits work.) The woman controlling my access to accommodations was worried, essentially, that I was not as committed to my job as others.

Similarly, I have sometimes struggled to be seen as committed to writing because I do not write daily or produce work as consistently as others I know. Within the MFA, I rarely felt “enough” compared to others, especially when the community preached the importance of having a practice that proves that I am putting writing first. In other areas of my life, people love to converse about how young someone is when they first publish and how much work they must have put in. I am well aware that, in some ways, I am a fast writer; I am also well aware that my speed is inconsistent, and we live in a society that always wants content. If I am not writing enough, I am also not publishing enough. Thus, I am not impressive or providing enough value to my readers. Thus, I am not to be taken as seriously as I would have been if I were abled.

The truth is, others are not always on crip time; they expect everyone to arrange their time as they do, and judge others when they do not. The outcome of such pressure isn’t only the impact on disabled people’s careers but also the fracturing of self-confidence and self-worth. (I will pause here and point out that yes, self-worth is our own job to cultivate. Yes, no one can make us feel less than unless we let them. And also yes, it is hard to feel good about yourself when you do your best and yet that effort is undervalued not only be the structures we live in by the people you hold in high esteem.) All too often I have discussed loving myself and my capabilities with my therapists. All too often they have asked me if I am resting enough, if I am taking on too much, if I am trying too hard to be someone I am not. All too often I go back to wondering how much more I could do if I wasn’t sick. As Samuels says, “with each new symptom, each new impairment, I grieve again for the lost time, the lost years that are now not yet to come.” I would add to that, I grive, too, for the projects I might never do, the art I might never make, because I can’t get there fast enough.

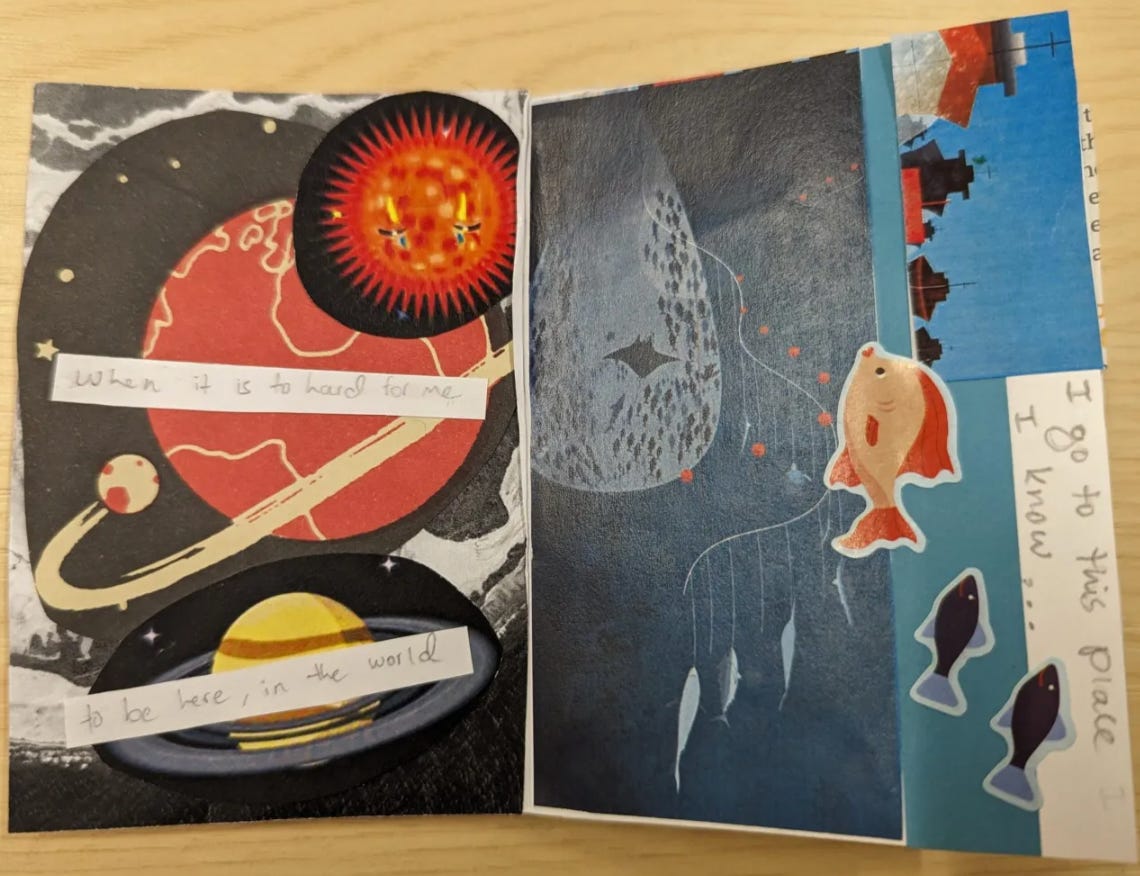

But Samuels also writes “disability scholars like Alison, Margaret, and I tend to celebrate this idea of crip time, to relish its non-linear flexibility, to explore its power and its possibility.” And in an essay titled “MedHums 101: What is Crip Time?,” Élaina Gauthier-Mamaril explores the generative qualities of crip time as well. Powerfully, Gauthier-Mamaril discusses that crip time as a time of dreams. She points out that creative thinking is an inherent part of being ill—disabled people need to get their basic and more complex needs met in ways outside the norm—and because of this, innovation is required. It is not so different, perhaps, than when a writing instructor suggests their student place restrictions into their work (i.e. write a poem without using the letter ‘t’) to open new possibilities and commit to doing things as they were not done before. As I see it, learning to think outside of the norm is practice, and once we practice enough, we start to bring this way of imagining into all areas of our lives—even our writing.

Interestingly, Gauthier-Mamaril also discusses commitment as an aspect of crip time, but she looks at committing to the unpredictability of illness as “a refusal of compulsory productivity.” I agree with this—and I am critical of capitalism as she is—and yet artmaking sometimes requires a logistical level of doing. A book has to be written to exist. It has to exist to be part of a conversation—which is why I, at least, write. It is why many of us write. We want our ideas to engage with others and vice versa. In this letter to you, I have written about the capitalist side of writing and publishing, but both because of its content and because of the very act of writing to you, to reaching out this way, there is also a hint of someone who desperately wants to be heard through her writing, and worries she cannot always commit enough to making that relationship between herself and readers. On one side, there is compulsion, but on the other, there is desire. If I intersect that latter concern—which is far more focused on relationality and community than fame; and is thus more about the joys of connection than the woes of not being noticed by the “right” people—with Gauthier-Mamaril’s thinking on the generative, creative thought brought on by crip time, I find myself at much greater peace.

If crip time is committed and uncommitted time, it is valuable to consider how disabled people commit to the reality that there is a tension between who we are, who we want to be, and who we are expected to be. Not only do we recognize this for ourselves, but we can also dream of how this tension exists for others—whether they are disabled or not. Living inside crip time is what allows me to tell stories of others at similar crossroads. And so, even if all the time in the bathroom, the minutes that feel wasted on illness, take over, it isn’t for naught. That crip time can feel like a barrier to “success” is exactly what is needed for me to make my art. Because what is generated in crip time is a commitment to considering what it means to live like this. Not just for me to live like this but for anyone to live in such complexity. What crip time requires is a then a commitment to empathy, more than anything else. And that, of course, is what makes a story. That, more than how much time it took to write it.

A Healthy Dose of Updates

Ravishing

Ravishing is headed to copyedits! Cover discussion is happening! All of this is very exciting—and as a debut novelist, very new.

Right now, the best way to support the book is continuing to subscribe to this newsletter (and sharing it either by forwarding it or talking about it on social media!) as well as following me on my socials. I’m on Twitter/Instagram as @__eshani and Bluesky/TikTok as @eshanisurya.

Other Things

I’ve joined the board of Blue Stoop, a fantastic literary organization in Philadelphia! Check out our free resources, classes, and more at the website. Also, consider donating if you’re looking for a cool way to support writers.

xx,

Eshani