Dear friends,

I’ve always worried about how to say everything right, even in a story. Do these character make sense? Is there an arc? Will everyone understand what I am trying to do? What even am I trying to do?

This week my story “A Hundred Orbits” was published at The Rumpus after eight years since I wrote its first draft (I’ve actually recalculated since I made this claim on Twitter and it may be seven years instead—regardless, somewhere around three-quarters of a decade). Though it isn’t the first time I’ve written work focused on ulcerative colitis/inflammatory bowel disease (see: “Between the Colitis Flares…”), but the story holds a long history. “A Hundred Orbits” is the story I wrote just a month after I was officially diagnosed with ulcerative colitis. I was a senior in college, taking my last creative writing workshop, and I’d just been told I would be dealing with this bleeding, this diarrhea, this fatigue, off and on for the rest of my life.

I remember at some point my mother said, on the phone, “You must be wondering: what has happened to my life?”

I was. I ruminated on that question almost daily after she said it.

I used to say I didn’t know why I wrote fiction, that I did it because someone somewhere told me I was good at it. That I chose to write my first workshop story that semester about my new illness—all of it written in a desperate flurry over the weekend—indicates that I am part of a particular writerly narrative that I am not sure any of us can escape. The process of writing is the process of processing. What I mean to say is that by writing a story, I give myself control over the narrative, over the chaos of my own life. I fit things together through words. Every story is a self-made jigsaw puzzle, solved in tandem with its conception. So though I am writing for other people (what is publishing if not asking for an audience?), what I am suggesting is for them to ask the same questions I do, not for them to learn about something I know unequivocally to be true.

When I wrote this story senior year, it was called “Gut Flora,” a title I liked because it tied together something beautiful with something ugly. Strangely, I chose to write about a teenage white girl, Emma, living in the suburbs. Her cousin, Adelaide, was visiting for the summer, but had no knowledge of Emma’s illness. In the pivotal last section, the story lists out Emma’s most pressing concerns:

“I’m fine,” Emma said, though she was not, though she couldn’t climb on top of Max and do what he needed her to do; though her mother was not home to comfort her; though sometimes her mother did not feel like her mother, because she cried sometimes after doctors appointments; though her stomach hurt, it hurt all day now, even if she avoided ice cream and coffee; though it didn’t matter how thin she was because no one could love a girl who bled so hard; though her cousin would leave in two weeks and she would be alone again with just the colitis holding on.

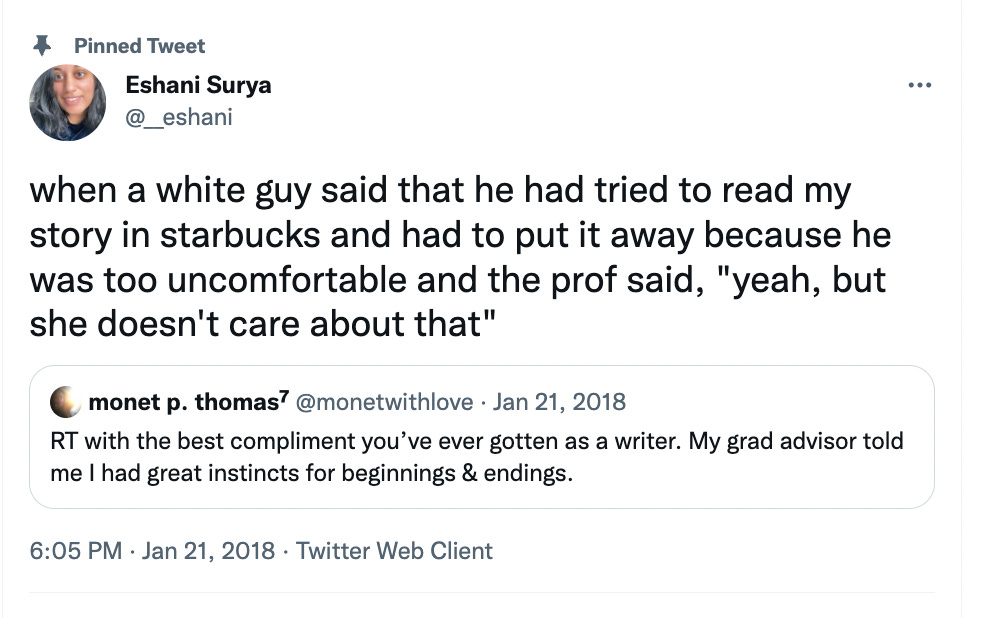

The echoes of what the story wanted to say, still wants to say, linger in that paragraph. Mostly because that was why I wanted to say a month after diagnosis. (The fun of keeping old drafts is being able to go back to them years later and see exactly what heart the story still has, what engine it has always needed.) In workshop, there was awkwardness. Many of my peers didn’t know how to discuss the story, but some really liked the writing. A few thought it was too visceral, too gross, but I had my defenders.

At a critical juncture, the professor asked if the story felt realistic to the class, a stupidly phrased question, but a question nonetheless. (I think he would have been better off asking, “Did you understand the arc of this story and character? What clarity did you feel you needed?” especially assuming that most of the class did not have personal experience with ulcerative colitis. I rarely ask my students if something is realistic for this reason - and I would challenge why it even matters if something is realistic at all when our realities are often so disparate from each other’s. Even within the field of medicine, each treatment plan varies, just as individual reactions to medication vary, and we’ve come to respect that in the online forums/communities I’ve joined. What is real for me is often not at all real for a patient with the same diagnosis as me. In the same way what is real for me when I walk down the street in my Indian body is not the same for my white husband, even when we go hand in hand.)

After the poorly phrased question, one girl leaned back in her chair and said, “I have colitis and this is nothing like it.”

I went hot. The entire room stared at me, like they wanted to take their compliments away. I’d made up everything, they assumed, and badly. Breaking all workshop etiquette I said, clearly tearful, because I was not yet ready to disclose it in the way that I am now, I said, “I have it too.”

Maybe that is why I wrote the story from the perspective of someone so unlike myself. Maybe I wasn’t ready to give all of myself to the page, or maybe I hadn’t lived enough of the story to ask real questions about myself instead of a supposed girl who reflected me, but also all the stories I’d read about colitis through the Internet. (That, and I don’t think I knew I could write stories about brown girls at the time. Writing white was my default, even by the end of college.) That girl who’d spoken up in workshop tried to talk to me about my own colitis later in the bathroom, and I escaped as fast as I could.

Time passed. I went into remission. I used the story as part of my application package for MFAs, now called “Behind the Woods,” with this as an anchor to the story:

Adelaide laughed in a way she didn't laugh in front of boys or her parents. She laughed like she used to when Emma proposed they go exploring in the woods behind the house. Past those bushes must be something exciting, Emma had said, and Adelaide had laughed and laughed and said: behind the woods there are only woods, Em.

&

While she sat on the toilet, she catalogued. Purple towels, shower curtain neatly folded into the tub, lilac-scented soap, like always. 11:06 PM, pain. How much, on a scale of 1-10? Yes, 10 being the highest. 7. Blood. No enema. Dark mucus. More blood. When she’d finished, she looked out the window. The woods stretched far back, past the borders of their property. She wondered if she could go running in them, wondered how far they would take her before she found something worth stopping for. Behind the woods, there are only woods, Em.

Again, an engine revealed, but perhaps not fully realized. I was accepted to school, but I didn’t revise the story after. I didn’t pursue publication. I knew the story needed work, but I wasn’t sure what. I wanted it to say all the ways I’d been shaped by my disability, but how?

In 2019, my colitis flared again. I was hospitalized twice because my body couldn’t process the medication I was put on. I lost all my hair. I went into remission again after my immune system was wiped out. In 2021, I flared yet again. This time, nothing was making a difference, not even a high dose of steroids. I couldn’t eat dinner without running to the bathroom twice. It is hard to compare periods of illness, but this felt like the worse it had ever been. I turned, again, to “Behind the Woods,” and wrote in the same desperate flurry I had years before.

The story I published is still fiction, but I wrote it to be much closer to myself. In “A Hundred Orbits,” an unnamed college student lives with her roommate and contends with her newly diagnosed illness. She and her roommate take care of each other in all the wrong ways. She is Indian, considering a naturopathic approach alongside an allopathic one. She thinks she might be making too many mistakes. She loves someone who loves her who she hopes will keep loving her. (Since I wrote “Gut Flora,” I fell in love and, at that time, had to decide how to confess my illness to my now-husband.) She wants to be beautiful. In the end, it is a specific story of one person with ulcerative colitis. It about the early days after diagnosis, but I wrote it years after that time in my life, with more salient knowledge of drugs and treatment plans, but with more wisdom of the trauma that I had yet to articulate at that time. It does not say everything I feel or everything I think I know, at least at this time. It is not everyone’s story, even though I sometimes think people expect it to be. Maybe people want it to be emblematic of not only the way ulcerative colitis is, but also how all chronic illness plays out for sick people, not unlike how race narratives or queer narratives are often taken out of context as the end all be all of what it is to be a certain identity.

The truth is, there is a lot in “A Hundred Orbits” that is not my story at all, at least when it comes to plot, but it is mine when I think about how lonely it is to try to figure out what the right thing to do is after your body has betrayed you. That was all I was trying to do; that was all that was done.

xx, Eshani